Oregon Women Protest for Suffrage:

National Woman’s Party Members in Oregon and in Washington, D.C., 1917-1918

Oregon women members of the National Woman’s Party (NWP) engaged in voting rights activism by adopting a more radical stance than members of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Established in 1913 by Alice Paul and Lucy Burns as the Congressional Union and renamed the NWP in 1916, members lobbied for a federal suffrage amendment. They worked against the political party in power nationally (the Democrats, under President Woodrow Wilson) in state elections where women were voters to support candidates who favored a suffrage amendment.

During the First World War, NWP members gathered in Washington, D.C., to picket the White House in silent protest. Known as the “Silent Sentinels,” they carried signs that challenged Wilson’s statements that the United States had entered the war to “make the world safe for democracy.” How, they asked, could the nation claim to be democratic when many women were not able to vote? The Wilson administration worked to assure loyalty and support for the war effort and Congress passed the Espionage Act in 1917 to criminalize and penalize criticism of the war effort. Police arrested hundreds of pickets and sent many to the Occoquan Workhouse in Northern Virginia where the women experienced harsh treatment and poor conditions. Many chose to protest these conditions by hunger striking. Protests continued through the end of the war. Further Reading

Students in Professor Kimberly Jensen’s Women in Oregon History class at Western Oregon University in Spring 2019 researched the Oregon women of the NWP who participated in active protest for a federal suffrage amendment. We present information about them here. Sisters Alice and Betty Gram were arrested for picketing the White House in November 1917 and hunger struck in the Occoquan Workhouse. Dr. Florence Sharp Manion and Emma Wold, officers in the Oregon Branch of the NWP, protested from Portland by writing letters to President Wilson and other officials. Clara Wold, Emma’s sister, was arrested in August 1918 for occupying a statue in Lafayette Square across from the White House.

Alice Gram and Betty Gram

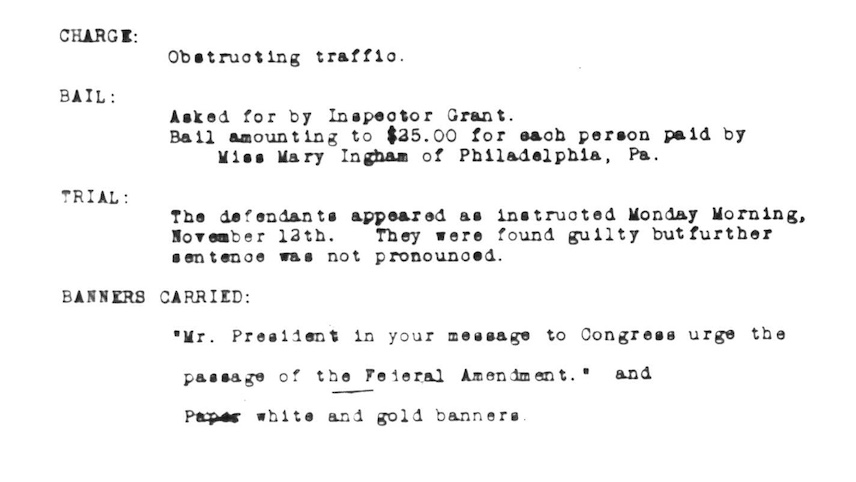

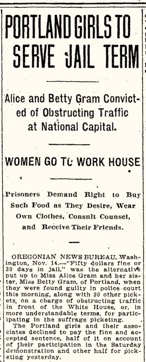

Portland sisters Betty and Alice Gram were among the forty-one women representing sixteen states arrested for picketing the White House on Saturday, November 10, 1917 in support of an amendment to the U.S. Constitution for women’s voting rights. Betty, at 24, had attended Portland’s Jefferson High School and the University of Oregon and had been a teacher. Alice, at 22, had become a journalist while attending Jefferson High School. On the day they picketed the White House President Wilson was scheduled to deliver a State of the Union Address on December 4. The pickets carried a banner that read “Mr. President in your message to Congress urge the passage of the federal amendment.” The charge for the arrest of the silent, non-violent women picketing in protest? Obstructing traffic.

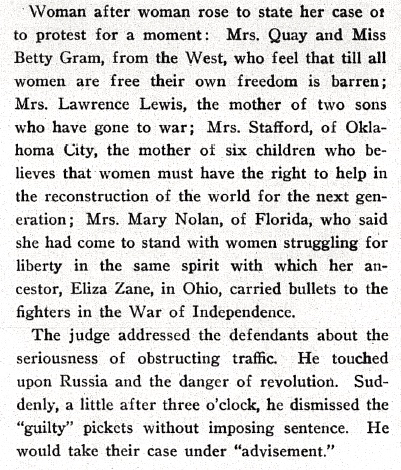

Betty and Alice Gram appeared at court on Monday morning, November 12, and with the other pickets plead “not guilty.” Betty Gram spoke at the trial. As the editors of The Suffragist noted, she was among “woman after woman” who “rose to state her case or to protest for a moment.” Gram and Minnie Quay, from Utah, spoke as enfranchised women from Western states. They felt that “till all women are free their own freedom” was “barren.” Judge Alexander Mullowney found all of the women guilty while discussing “the danger of revolution” as part of his decision. But he released them to return for sentencing later in the week.

That same day, Monday, November 12, the Gram sisters returned to the picket line with the same banner and were again arrested on the charge of obstructing traffic. They were sentenced to 30 days in the Occoquan Workhouse when they refused to pay a fifty-dollar fine.

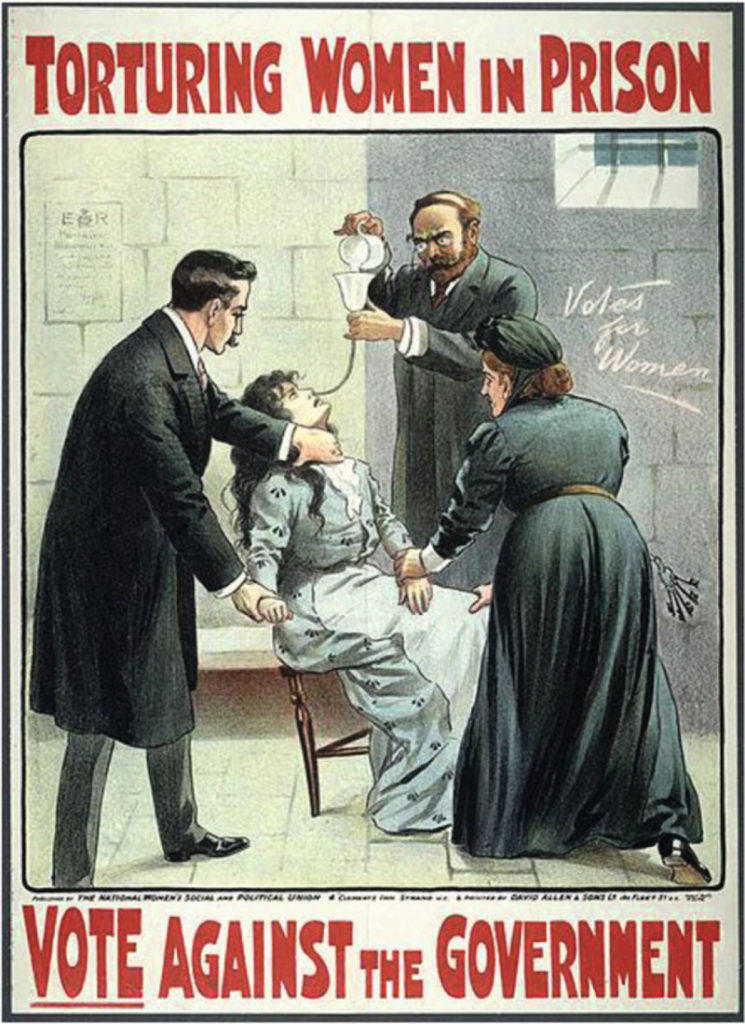

Both Alice and Betty Gram chose to hunger strike with other pickets at Occoquan. They joined NPW president Alice Paul and other pickets imprisoned in Washington, D.C., and followed the strategy of British suffragists who engaged in hunger strikes as protest when imprisoned. Like British officials, wardens at Occuquan and in D.C. force-fed hunger strikers. They were released after almost two weeks, on November 27, 1917.

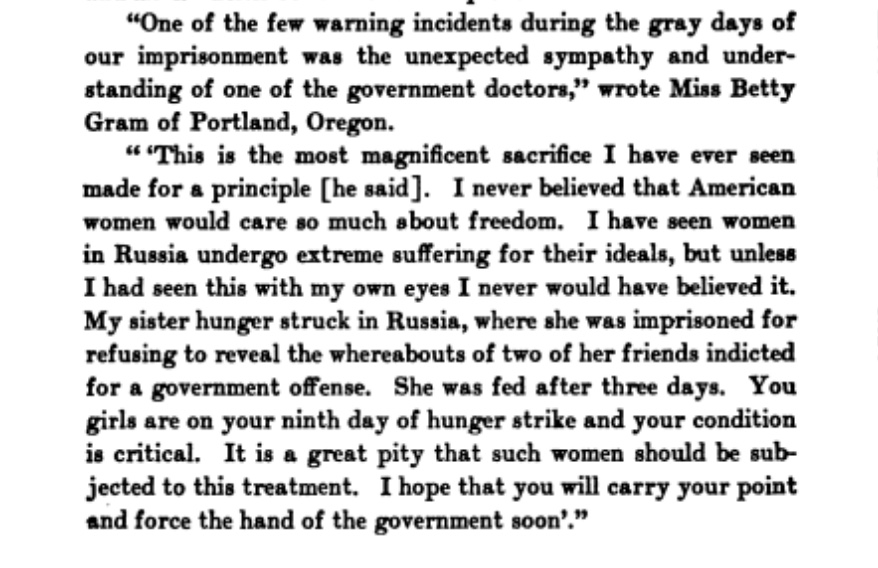

In Jailed for Freedom, Doris Stevens recorded Betty Gram’s recollections of hunger striking and force feeding. Gram recounted the words of support she received from a physician at Occoquan.

The bravery, persistance, and willingness to hunger strike under conditions of force feeding by suffrage activists Alice Gram and Betty Gram and the other “Silent Sentinels” helped to turn public opinion in favor of votes for women. This editorial cartoon by Nina E. Allender from The Suffragist shows a suffrage picket in prison in the District of Columbia with a banner reading “How Long Must Women Wait for Liberty?” with public opinion, the “court of last resort,” shining a favorable spotlight on her sacrifice.

Dr. Florence Sharp Manion and Emma Wold

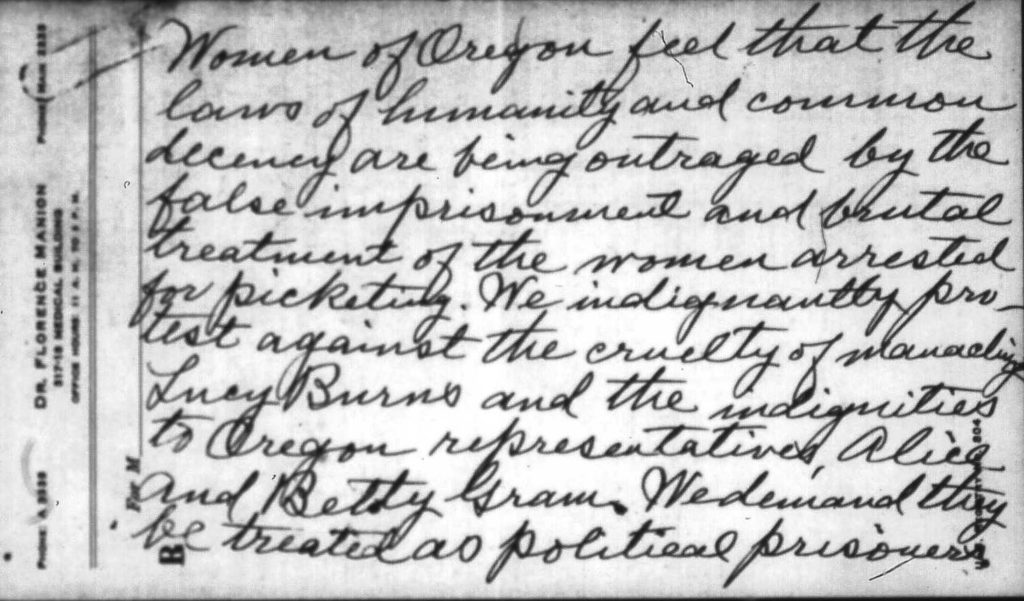

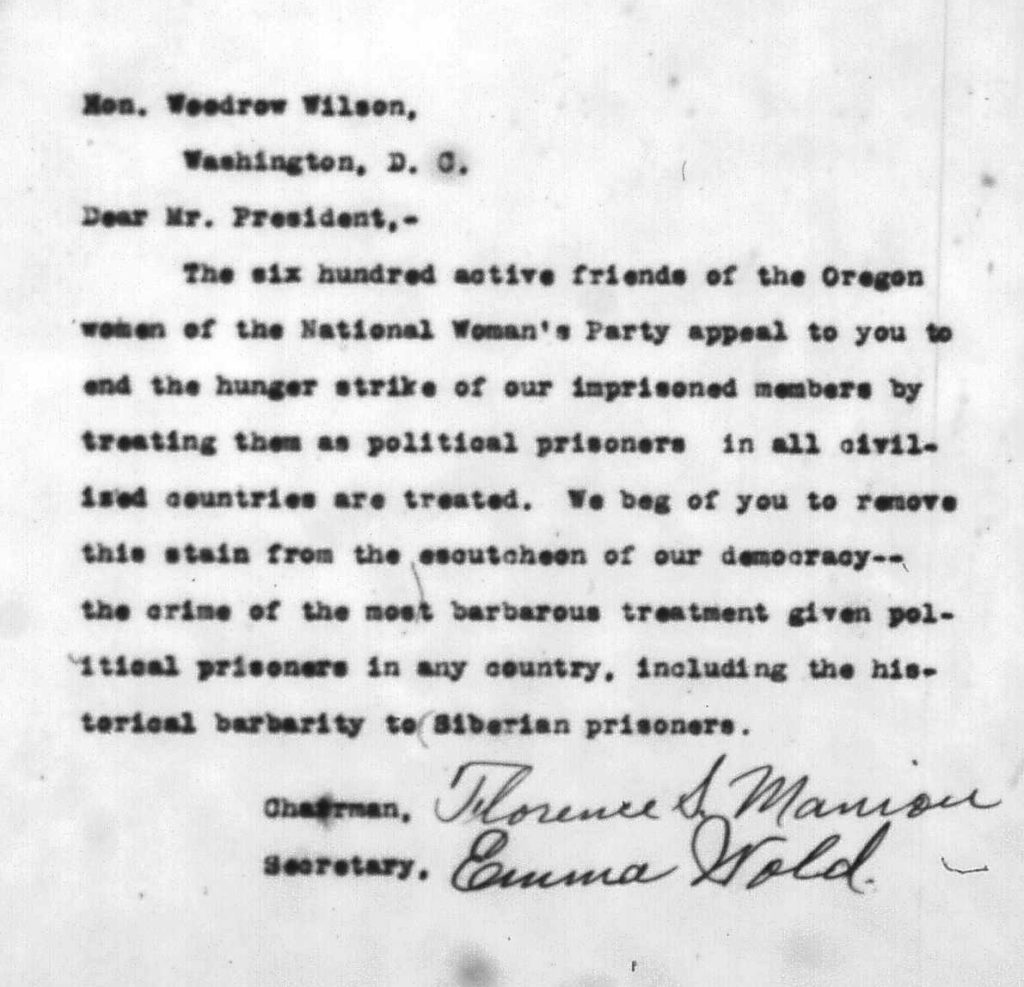

Dr. Florence Sharp Manion chaired the Oregon Branch of National Woman’s Party at the time Alice and Betty Gram were protesting in Washington, D.C., in 1917. On November 17, 1917 she wrote to Virginia Arnold at NWP Headquarters in Washington, D.C. Her message underscores how radical the pickets were.

“Am enclosing a copy of message sent to President Wilson, cabinet members and commissioners as requested in your message of today. Also clippings from local papers, we have very little sympathy here.

“I wish we might be relieved from the burden of imprisonment. My heart aches for Miss Paul.”

Manion used her prescription note pad to make a copy of the message she sent to the President and other elected officials:

“Women of Oregon feel that the laws of humanity and common decency are being outraged by the false imprisonment and brutal treatment of the women arrested for picketing. We indignantly protest against the cruelty of manacling Lucy Burns and the indignities to Oregon representatives Alice and Betty Gram. We demand they be treated as political prisoners.”

Emma Wold graduated from the University of Oregon and worked with the College Equal Suffrage League. As Secretary of the Oregon NWP, she joined Florence Manion on another message to President Wilson in November 1917, protesting the treatment of the imprisoned hunger strikers. Manion and Wold put pressure on public officials from their posts in Portland by writing letters to support Alice and Betty Gram and the other suffrage activists picketing and in prison.

Clara Wold

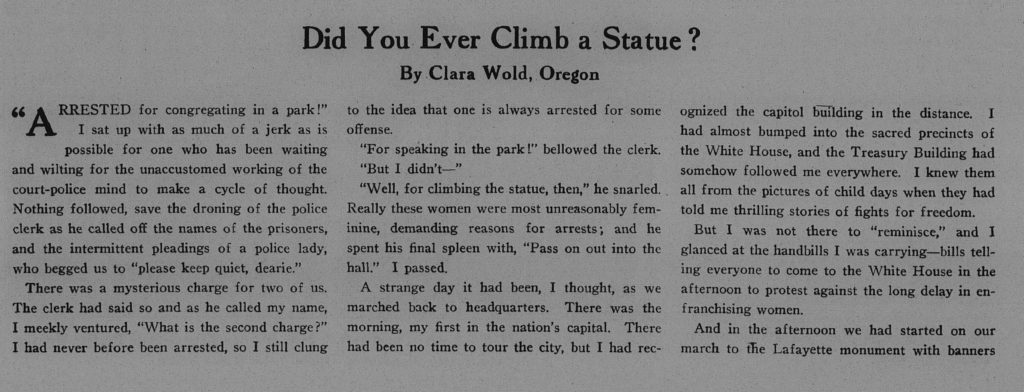

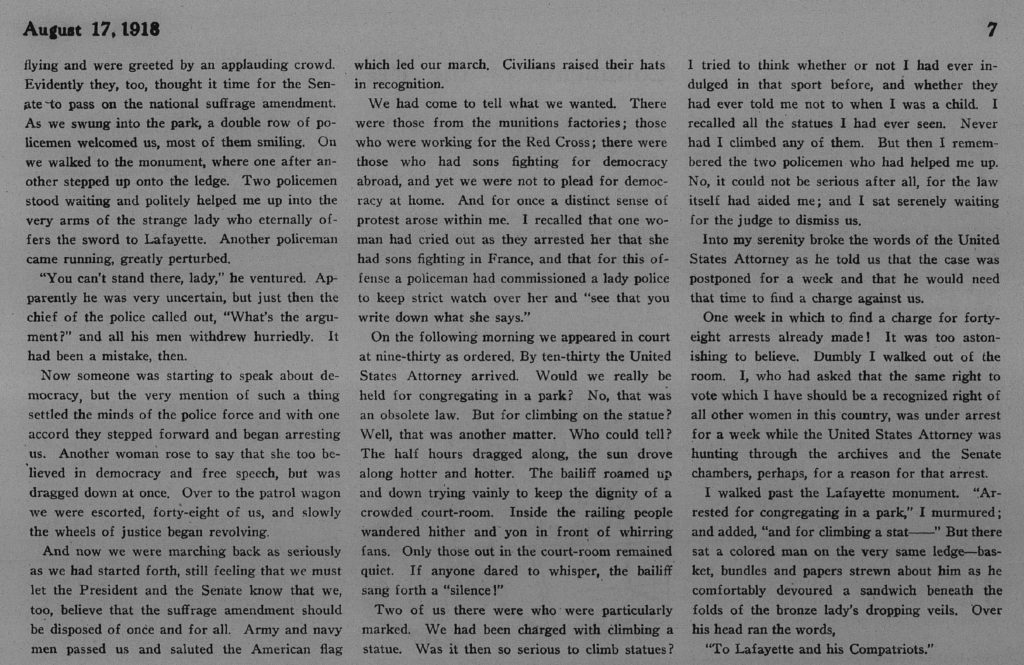

NWP activist Clara Wold, Emma’s sister, came to Washington to participate in the protests in the summer of 1918. In August she was arrested for protesting in Lafayette Square, the park directly across from the White House.

Clara Wold published an account of her arrest in Portland’s Oregonian newspaper: “Clara Wold Tells Story of Her Arrest,” Sunday Oregonian, August 25, 1918, Section 1, page 15. She published the same account as “Did You Ever Climb A Statue?” The Suffragist, August 17, 1918, 6-7. She discussed how ridiculous she found the situation and especially that the court could not find charges against her.

We spent time discussing the importance of Clara Wold’s protest, and how clear it was that her arrest was for her political views and not her actions. We also took the opportunity to talk in detail about the last paragraph of her account. She wrote about walking past the statue of the Marquis de Lafayette, who had assisted the American Revolutionaries in their fight against Britain. She was pondering her arrest “for congregating in a park” and “for climbing a statue.” And she concluded her account this way: “But there sat a colored man on the very same ledge–basket, bundles, and papers strewn about him as he comfortably devoured a sandwich beneath the folds of the bronze lady’s dropping veils. Over his head ran the words, ‘To Lafayette and his Compatriots.'” Wold appears to be saying that a Black man was able to sit undisturbed at the statue while she and other women were arrested for being there, and therefore White women suffrage activists had fewer rights than Black men. Here she introduced race, class, and gender questions and a divisive ending to her account. The movement was most successful when activists were inclusive and worked for the rights of all. Race and class divisions limited the power of change for gender equality.

Alice and Betty Gram, Florence Sharp Manion, and Emma and Clara Wold were among the many Oregon women members of the National Woman’s Party who protested federal inaction regarding a woman suffrage amendment to Congress. They risked censure, arrest, and imprisonment during their First World War-era protests. Their radical actions had a strong impact on public opinion and helped to achieve the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. As enfranchised citizens since achieving the vote in Oregon in 1912, they worked for the cause of women across the nation. As Betty Gram testified at her trial in November 1917: “till all women are free their own freedom” was “barren.”

Alice Gram Robinson was founder of the National Woman’s Press club in 1919 and established the Congressional Digest in 1921 and served as the publication’s president until 1983. She died in 1984. See biographical information in Papers of Alice Gram Robinson, Schlesinger Library, Harvard University: https://hollisarchives.lib.harvard.edu/repositories/8/resources/7124

Betty Gram Swing worked on the staff of the NWP newspaper The Suffragist and was a paid suffrage organizer. After the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment she moved to Berlin to study and married journalist Raymond Swing. She and her family returned to the United States and in the 1930s she served on the national council of the National Woman’s Party. She died in 1969. See biographical information in Papers of Betty Gram Swing, Schlesinger Library, Harvard University: https://hollisarchives.lib.harvard.edu/repositories/8/resources/8259

Dr. Florence Sharp Manion was a respected physician in Portland and practiced until her death in 1937. See “Rites Tomorrow for Dr. Manion: Woman Physician in Practice Here for 40 Years,” Oregonian, December 12, 1937, 34.

Sisters Emma, Clara, Jean, Gaeta, and Cora Wold were all involved in woman suffrage activism. Their grand-niece Priscilla Longfield, is engaged in researching and writing about their lives. Emma Wold graduated from the University of Oregon and Washington Law School. In 1921 she served as national chair for the Women’s Committee on World Disarmament and served in various capacities as a legal consultant and expert at the International Court at The Hague. She died in 1950. See “Dr. Wold Dies, Former Resident,” Eugene Guard, July 23, 1950, 5. Clara Wold graduated from the University of Oregon and worked in journalism. She served for a time as editor of the NWP newspaper The Suffragist. She died in 1923. See “Clara Wold, Writer Dies in Europe,” Eugene Guard, April 5, 1923, 8.

And for additional information see:

“Forty-One Suffrage Pickets,” The Suffragist, November 17, 1917, 7.

Jensen, Kimberly. “Woman Suffrage in Oregon.” The Oregon Encyclopedia: https://oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/woman_suffrage_in_oregon/#.XPfM2Px7nq4.

Jensen, Kimberly. “Women, Politics, and Power.” In Oregon’s Doctor to the World: Esther Pohl Lovejoy and a Life in Activism. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2012: 98-121.

Jones, Mark. “The Silent Sentinels.” Boundary Stones, WETA Local History Blog, March 19, 2017: https://blogs.weta.org/boundarystones/2017/03/19/silent-sentinels.

Korges, Wilson. “The Lasting Legacy of Suffragists at the Lorton Women’s Workhouse,” Smithsonian Folklife Magazine, March 21, 1918: https://folklife.si.edu/magazine/lasting-legacy-of-suffragists-at-lorton-occoquan-womens-workhouse.

Lunardini, Christine A. From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman’s Party, 1910-1928. New York: New York University Press, 1986.

National Woman’s Party, “Our Story”: https://www.nationalwomansparty.org/our-story.

Report of the Demonstration Department Month of November 1917, p. 2 of 8, Frame 105, Reel 87, Demonstration Department June 1917 to November 1917 Administrative Files 1913-1921 National Woman’s Party Papers, The Suffrage Years, Library of Congress. Microfilm Copy at the University of Oregon Knight Library, Eugene, Oregon.

Stevens, Doris. Jailed for Freedom. New York: Boni & Liveright, 1920. Digital copy available at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044087355707;view=2up;seq=240

Women of Protest: Photographs in the Records of the National Woman’s Party, Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/collections/women-of-protest/about-this-collection/